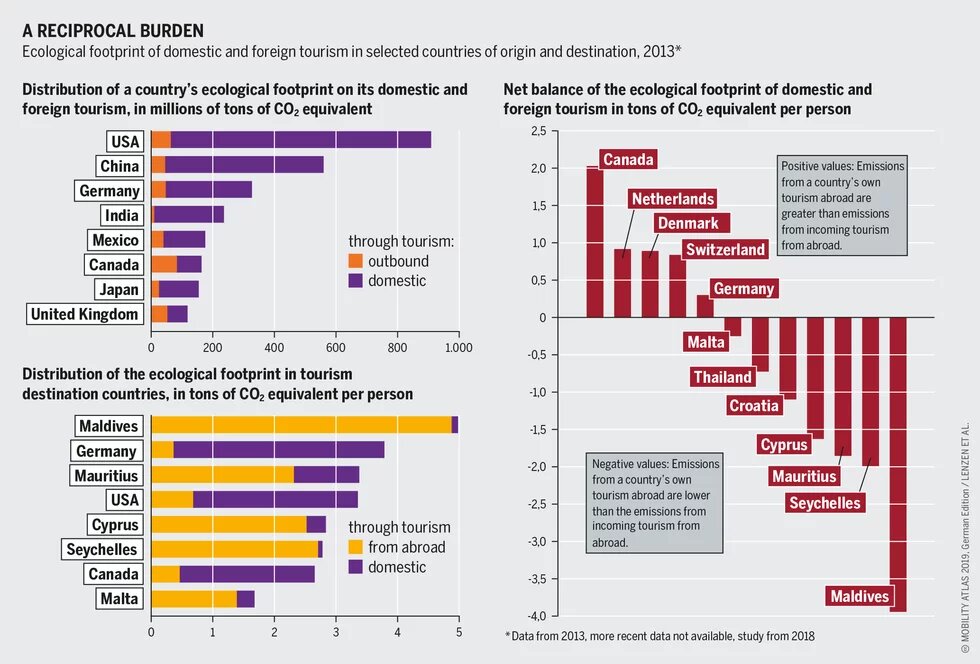

The type of travel and local tourism management determine how sustainable a holiday can be. Environmentally friendly offers are on the rise, but above all conventional forms that ignore environmental pollution are booming.

The number of people who want to and can travel is increasing. In 2018, 1.4 billion trips abroad were made worldwide, six percent more than in the previous year. Experts expect 1.8 billion in 2030, a third more than today. In the past, travel was a privilege of the rich. Today many people have the opportunity to get to know other countries and cultures. Travel and tourism can therefore contribute to international understanding and economic prosperity in the regions visited.

Nature and culture - for tourism, both should be accessible and preserved at the same time. This can only succeed if holiday travel becomes socially acceptable and ecologically sustainable. There are many factors that determine this: the arrival and departure, also the way tourists move around, what they consume and what they do.

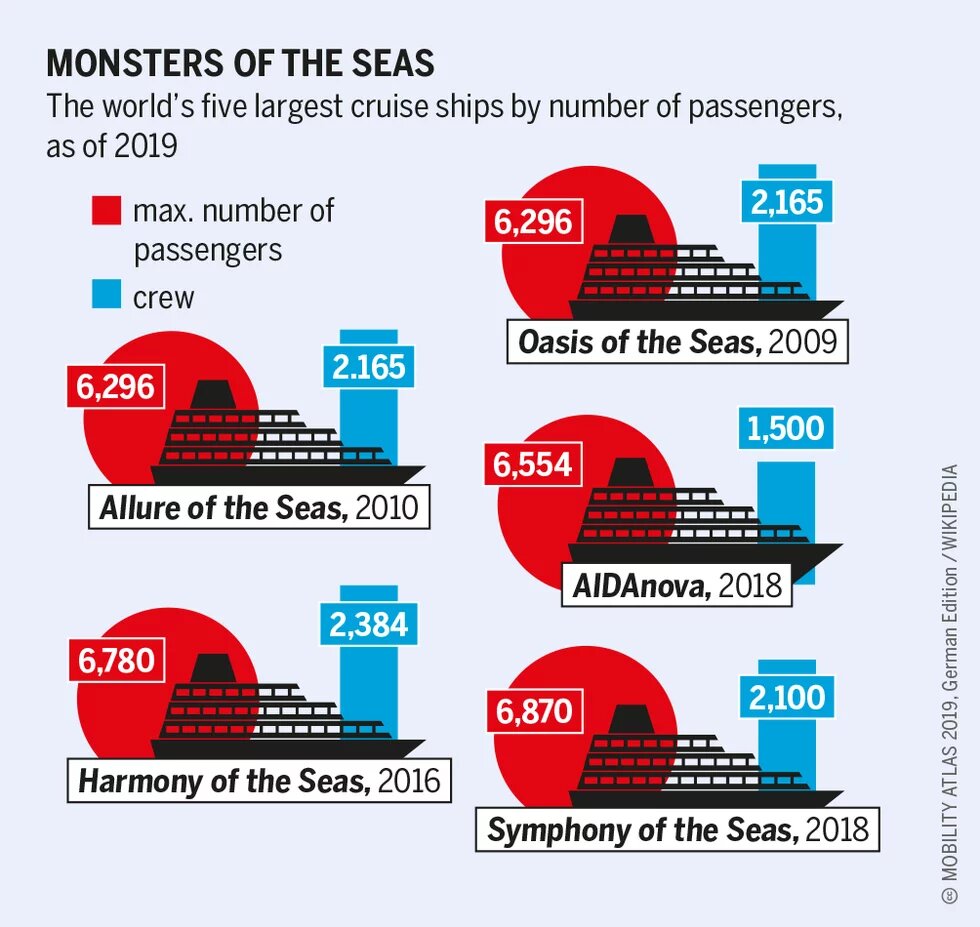

Cruises are considered a particularly environmentally damaging form of travel, alongside flights on holiday. Most ocean liners use heavy fuel oil as fuel, which is so harmful to the environment and health that its use in inland waters is prohibited. Shipping companies and industry associations want to act more environmentally friendly, but environmental associations are sceptical. So far there is only one cruise ship that runs on liquid natural gas (LNG). The exhaust gases are cleaner, but liquid gas is also a fossil raw material and its use is not climate-neutral. In some ports, for example in Hamburg, shore power plants can supply ships during their berthing time in order to avoid exhaust and noise from diesel operation.

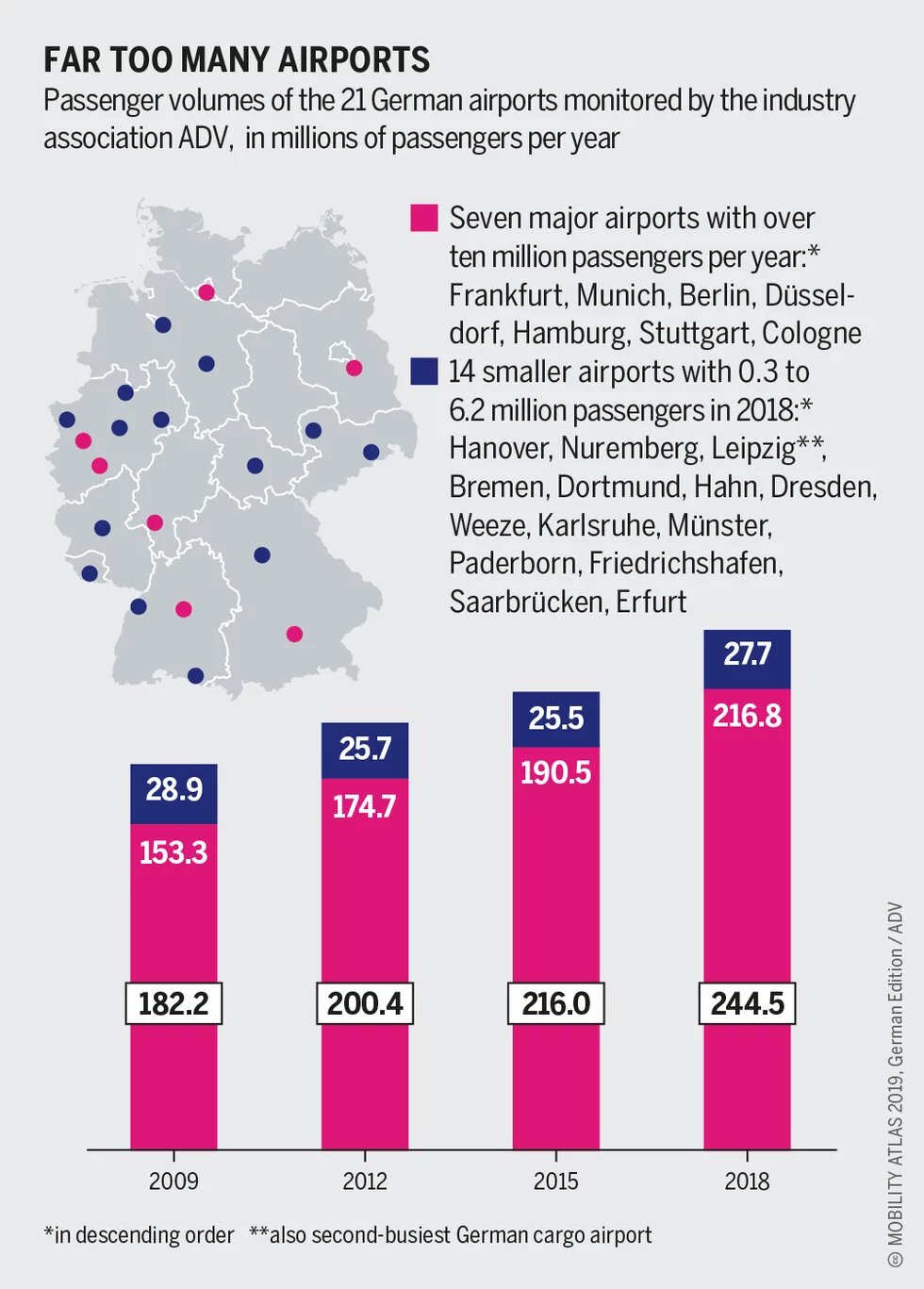

Global air tourism is growing faster than all air traffic, including business travel and freight transport. One reason is that the fast-growing middle classes of Asia and Latin America are now also increasing their use of holiday flights. Europeans are also increasingly aiming high: between 2012 and 2017, the number of tourist air trips grew by 15 percent. It is a long way until flying becomes "green". Fuel consumption per passenger has fallen by 43 percent since 1990. The industry is also experimenting with optimized flight routes, lighter construction, new fuels and more efficient engines. But these advances are being cancelled out because the number of flights is increasing much faster than per capita consumption is falling.

Some passengers voluntarily pay an additional fee for their flight to offset CO2 emissions. The revenues of Atmosfair, Germany's largest compensation provider, have tripled since 2015. The business is established, but controversial. Offsetting always remains only the second-best solution - compared to the goal of avoiding CO2 emissions completely or reducing them significantly. To achieve this, political measures are needed to make the alternatives to flying cheaper, more convenient and faster. New incentives are also needed to promote and accelerate research and development in the field of emission-reducing innovations for aviation and shipping. In addition, a kerosene tax would have to be introduced, subsidies for air transport and state aid for many airports would have to be stopped, and additional Europe-wide railway lines would have to be built as an alternative.

From the perspective of holiday destinations, tourism becomes particularly problematic if the number of overnight stays grows faster than the local population can react to it - for example in the case of closed resorts, where most business remains with the operator. In the case of cruise tourism, local value creation is particularly low because visitors do not have to book overnight accommodation or buy food locally and have little time for sightseeing. The city of Venice, for example, is left with nothing but rubbish, and its image is tarnished. As a result, the individual or group travellers who are eager to spend money stay away because of the crowds.

What can popular cities do against such "overtourism"? Experts suggest a mix of measures. Tourist flows should be distributed "more widely", both geographically and over time, and thus become more tolerable. Amsterdam's city marketing department promotes destinations in the vicinity of the city, for example "Amsterdam Beach", which is located in Zandvoort, 25 kilometres away. For Dubrovnik, which is also plagued by cruise ships, a website offers forecasts of when and how many visitors are expected, so that other tourists can find quiet times to visit.

Some places resort to more rigid measures. In Barcelona, there are strict regulations for private rentals and hotel construction, while Mallorca is fighting alcohol tourism. Iceland restricts access to a picturesque gorge to prevent damage caused by the onslaught of onlookers. And the Indonesian authorities want to close the island of Komodo all year 2020 to protect the monitor lizards, a species of lizard that lives there.

The UN World Tourism Organisation has drawn up a catalogue of 68 such protection measures. What actually works where often only becomes apparent after a few years. A lot of things take time, for example to develop a better infrastructure. Especially if sustainability is to be achieved in cooperation with the local population. After all, there are now more and more offers for sustainable holidays in Europe.