This article explores the degree of access to the key combating measures recommended by the World Health Organization with a specific focus on informal urban settlements. As a result, the dominance of crude power both by the state and policing mechanisms hindered the containment of the virus in grassroots communities.

On 13th March 2020, the Kenyan government documented the first case of the Corona Virus in Kenya. On 27th March, as a pandemic combating measure, the state imposed a dusk to dawn curfew, banned all inter-county travel and imposed COVID-19 prevention guidelines that soon became mandatory and punishable under the neo-colonial ‘Public Health Act’. Since then, the Kenyan population has seen an increase in state-sanctioned violence and authoritarian governance through violent policing and increased escalation by the National Police Service. All this was in favour of ‘pandemic policing’. However, to launch a war against a pandemic - that is invisible - means to target those who might be carrying it. In this case, the target was the poor and working-class communities primarily within urban-informal settlements.

Approximately four months into the pandemic, we had already seen a high number of cases of police brutality and over 15 police implicated deaths, which was a stark projection of what was yet to come. As seen in Kenya, pandemic policing ensures that in times of crises – such as pandemics – the key instruments of containment are ammunition and the prison systems backed by heavy fines and lack of education. Interestingly, the vast majority that continue to feel the brunt of pandemic policing are the working-class communities and wage labourers, primarily residing in urban-informal settlements whose primary interaction with police – as the centre of governance – has been violence.

This paper explores the degree of access to the key combating measures recommended by the World Health Organization with a specific focus on informal urban settlements. As a result, the dominance of crude power both by the state and policing mechanisms hindered the containment of the virus in grassroots communities. Pandemic combatting measures for many, became only survival tactics and not protection from the deadly virus.

The state failed to provide any of the stipulated prevention materials and services. It even went ahead to render Kenyans in urban-informal settlements homeless as the state enforced evictions in the middle of the night leaving many Kenyans easy victims to COVID-19 to continued state violence.

The main areas this paper focuses on is the chronic toll of the curfew and inter-county lockdowns, accessibility of masks, accessibility of clean water and finally, the adaptability of working from home. All through these areas, the fundamental similarity was the disproportionate classist discrimination and lack of care by the government. The language of war has infiltrated public health. In turn, pandemic combatting policies and solutions relied heavily on carceral and punitive measures that left communities in precarious positions.

Additionally, as the mandatory mask declaration was decreed, the executive arm of government was quick to ensure the execution of policing those who weren’t wearing mask and collection of fines that quickly turned to become extortion. These seismic laws and policies that were continually failing, failed to ensure the containment of the virus but instead saw the increased militarisation that adversely affected slum-dwellers and manufactured a sense of anarchy, especially in the informal urban settlements as police ruled by decree.

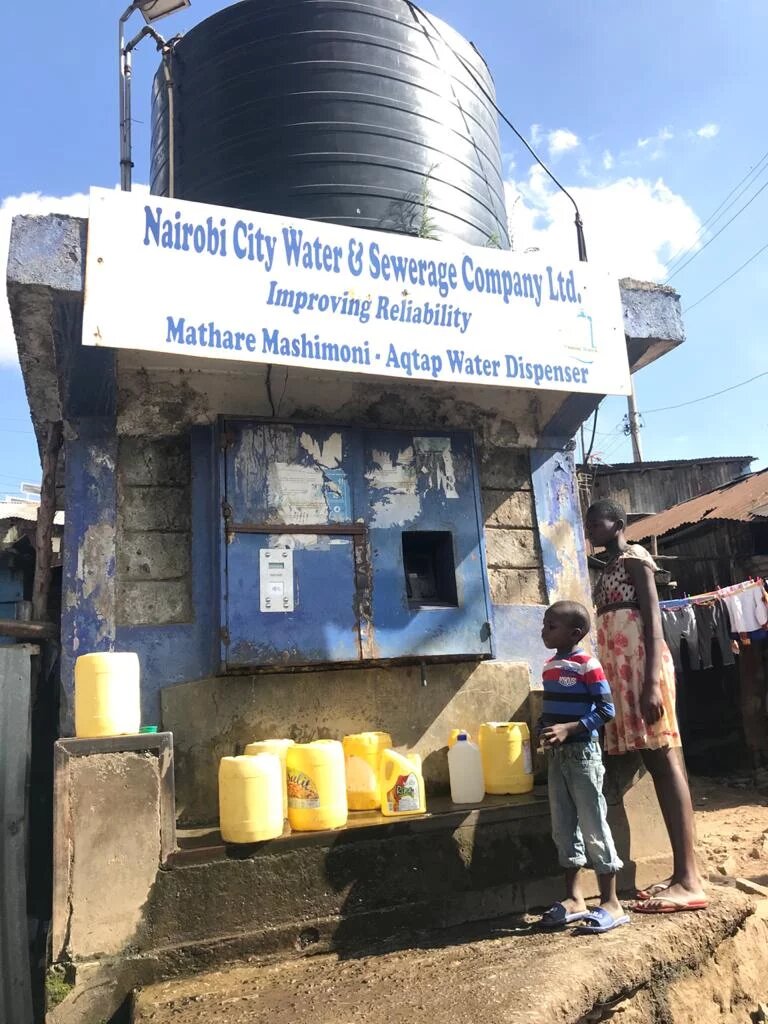

In terms of accessibility, this paper found that in grassroots settlements, through spatial management, are discriminately denied the most basic necessities such as water. This is primarily due to the increased privatisation of water pipelines by cartels and disregard by the Nairobi Water and Sewerage Company (NWSC) therefore making the most imperative need for survival and infection prevention widely inaccessible in these areas and an expensive commodity. Through the execution of this paper, areas like Mabatini Ward in Mathare had no access to clean, running water for almost a week, and at some point, the water they had access to was brown and smelly. This was a clear indication of necropolitics – who gets what to survive and who is denied – as there was no insistence on protecting the consumers who have no other sources of water.

Due to already overcrowded and congested living conditions, mechanisms such as isolation and social distancing were near to impossible in these areas. As the state continued enforcing one size fits all measures to combat – an unequal – virus, there was an apparent failure in the execution of these measures.

However, the rampant policing and militarisation during the deadly pandemic were not unfounded. Arguably, this was a mechanism to distract the residents within these zones from the continual lack of basic needs for survival and denial of infrastructure. Therefore, the heavy police presence creates a defacto ruling system of zonal managers within these areas. This violent presence, becomes the daily interaction between resident and government.

“During campaign season, they remember us”

Notably, during campaign season and election periods, candidates seeking elective posts remember these forgotten relics of state-violence.

Packed with handouts and well-equipped media teams, the remembrance and allocation of basic services and needs become a temporality of the state’s humanness. These politicians don’t do this because they care about the residents of Kayole, Mathare, Kibra or even the well-being of Kenyans, it is all weaponised manipulation to garner the attention of voters.

However, as visibly as the violence is in these areas, the structural divide clearly shows who feels the brunt of increased police presence. These articulated areas of concern and deliberate denials are a microcosm of the continued state violence faced by the Kenyan citizenry through the increasingly incumbent authoritarian regime. Pandemic policing seeks to individualise the violence of crises and further absolve the government from blame when the situation escalates, consequently seeing the citizens in proximity to the crises – such as COVID – as collateral.

A detailed paper available here by written by Suhayl Omar

Suhayl Omar is a Kenyan based researcher. His interests lie in theorising policing, surveillance, militarism and human precarity in Kenya's urban-informal settlements and beyond.