In Africa, fewer pesticides are used than in other regions of the world. Nevertheless the 33 million smallholders are increasingly becoming the focus of pesticide companies. There they also sell what has been banned in the European Union.

In 2015, the African agrochemical market was valued at about 2.1 billion US dollars. It accounts for only 2 to 4 percent of the global usage. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), an average of 0.4 kilograms of pesticides were used per hectare of cultivated land in Africa in 2019. This is less than the 3.7 kilograms in North and South America. But the African market for pesticides is projected to witness high annual growth rates, for example in West Africa. Pesticide use increased there by 177 percent between 2005 and 2015. In the same period total pesticide imports into the region roughly tripled, with particularly rapid growth in the three largest agricultural markets – Ivory Coast, Ghana, and Nigeria. Coupled with population growth, and the need to improve productivity, pesticide companies are increasingly seeing the 33 million small farmers on the continent as an attractive market.

Major players in the African pesticide market are Adama Agricultural Solutions, Sumitomo Chemicals, UPL Limited, and Bayer AgroScience AG. Companies use specific selling strategies to unleash market potentials in African countries. In Kenya, for example, social media, local radio stations, and broadcasts in local dialects are some of the most used mediums for product advertising. The documentary film “The Food Challenge” shows that prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, dominant pesticide companies frequently sponsored agriculture trade shows.

Depending on the crop, capital availability, and geographic location, farmers use pesticides very differently. Field studies from Mozambique and Zambia show the widespread use of Highly Hazardous Pesticides (HHPs) – according to a Michigan State University study, 76 percent of farmers in Zambia and 87 percent in Mozambique use them.

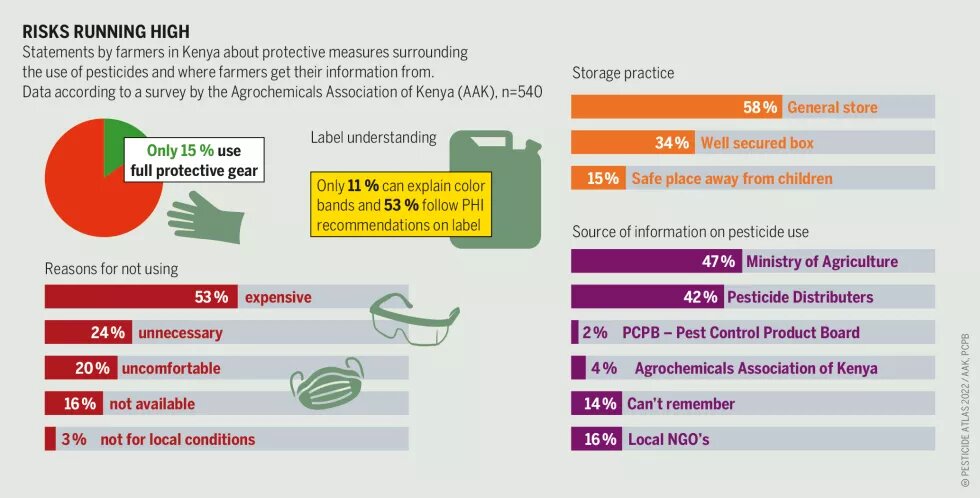

Small scale farmers and farm workers are particularly vulnerable when it comes to pesticide use. Mitigation measures are not practical because they are expensive or the farming context does not make risk management possible. In regions such as Africa, Asia and Latin America, smallholder farmers cannot afford proper backpack sprayers, masks, protective clothing, and gloves. In addition, buffer zones are not maintained because farm sizes are small and closely situated to each other and other homesteads. Pre-harvest intervals are often not known by the farmers or ignored because there is financial pressure to sell produce. Pesticides are also decanted from one container to another after they are bought from the agro-vet store, which means that instructions on how to use a product ‘safely’ have been removed. Civil society organizations blame weak regulations and the lack of information by industry for exposing farmers to these risks.

Small-scale farmers are highly exposed to toxic pesticides. They are not able to afford full protective gear or follow label instructions despite receiving information from the Ministry of Agriculture and pesticides sales agents

Further, different scientific studies show that pesticide markets in various African countries are not regulated in a way which protects farmers’ health and the environment. Another problem is that rules, laws, approvals, and controls could not keep pace with the increasing demand for pesticides – that is why a lucrative market for cheap generic and illegal pesticides has developed. Industry and academic sources estimate that up to 20 percent of the African market, and as much as 34 percent the West African market, are illegally produced and traded. In extreme situations, that number exceeds 40 percent of pesticides. Empty packaging and canisters are also filled with counterfeit products and sold as originals – with serious risks for farmers and the environment.

NGOs criticize a lack of safety standards in low-income countries. In Uganda every fourth shop sells repackaged pesticides

Civil society organizations are demanding stricter rules for pesticide market approval and authorisation informed by local data. They want governments to explore options to make regulatory risk data more transparent and accessible. Pesticide sales should be regulated and monitored accordingly, by independent authorities. Qualification criteria for agrovet sellers should be established and implemented.

Five in every six farms in the world consist of less than two hectares – which produce roughly 35 percent of the world’s food. In most cases the farmers suffer from poverty

Plant pathogens and pests are a major threat to the African farming sector, the incomes of producers and ultimately, achieving of the human right to food. Smart answers are needed to balance crop protection, which is necessary to ensure sufficient harvest, with human and environmental health: For example, investments in agroecological strategies and evidence-based knowledge sharing amongst farmers, experts, scientists, and policy makers. In some parts of the world this is already taking place. As a first step, organic farming has gained popularity for years. The organic acreage in the Middle East and in Africa is increasing as well. But these are only small steps on a long way. Even though scientists in the last years strongly point to the potentials of agroecological and organic farming methods these are still hardy supported by African governments.

This article was published in the Pesticides Atlas Kenya Edition.