A Call to Phase out Harmful Pesticide Reliance In Crop & Food Production

I want to refer to one of the most outstanding injustices in the colonial world. That is the injustice of the exclusive reservation for purely European use of the vast White Highlands in Kenya…”

30 October 1958 - John Stonehouse, Wednesbury MP 1957-1974

During the colonial era in Kenya, the agricultural sector was overseen by a retrogressive and racist colonial agrarian policy. It split into two main structures that saw the best arable land reserved for European ownership (referred to as the White Highlands) that concentrated on producing cash crops like coffee, tea and improved livestock mainly to be exported as commodities in short supply in Europe. In contrast, indigenous Africans were relegated to less arable land through these racist policies, with production mainly focussed on subsistence with surplus going to the market. Most of what they produced were food crops. The colonial policies kept Africans from profiting and gave preferential status to European settler farmers and their interests. Most Africans utilised an average of 5 acres and below, while European settlers would be allocated an average of 2,000 acres apiece.

In many ways, this was the rise of plantation farms and estates in Kenya. In post-colonial Kenya, many colonial relics remain intact in structure and objective despite ownership changing hands. In our fight for independence from the coloniser, there were calls for reforms to see more indigenous African farmers access better farmland. For many, this meant reclaiming their ancestral land and removing the prohibitions to grow export (cash) crops.

This context may partly explain why, once we gained independence, many small-scale Kenyan farmers tilted towards replacing their farms with food crops to cash crops like tea and coffee and improved livestock farming. After independence, Kenya saw agriculture as a significant avenue to build the economy, a sentiment that holds today. The new regime's challenge was to ensure that in the new dispensation, land and resources could be equitably redistributed in ways free from exploitative and extractive policies.

So, colonialists developed agricultural policies to favour their imperialist agenda. Regrettably, after independence, a handful of African elites took over and implemented a neo-colonialist agenda with reforms to benefit their narrow interests. It is, therefore, not by accident that smallholder Kenyan farmers lack economic and political clout to influence agricultural policy in their interest. On the other hand, large-scale and corporate farmers in Kenya have a considerable influence on government policies and markets.

Intensification of use and exploitation of existing farmland was seen as the primary method of achieving agricultural productivity, and this sentiment has been reflected in subsequent land and agricultural policies in Kenya since. Some of the elements of the new policies included encouraging smallholder farmers to cultivate cash crops. For instance, in Kenya, tea became the biggest smallholder cash crop. This led to the creation of KTDA to oversee the establishment and management of smallholders in the industry. Over the years, though, it is ironic to see that the parastatal and tea companies register high profits off the backs of Kenyan tea farmers.

Coffee is one of the world’s most traded commodities and a key cash crop, and Kenya is the fifth largest producer of coffee in Africa, with over 70 per cent of produce coming from smallholder farmers. It is very difficult to fathom that smallholder farmers of these premium crops in Kenya today still grapple with low prices and high input costs and are impoverished despite the crops being one of Kenya’s top export earners. Increased pests and diseases and land degradation have affected the crop production, with some key markets flagging our produce due to its high levels of chemical contamination.

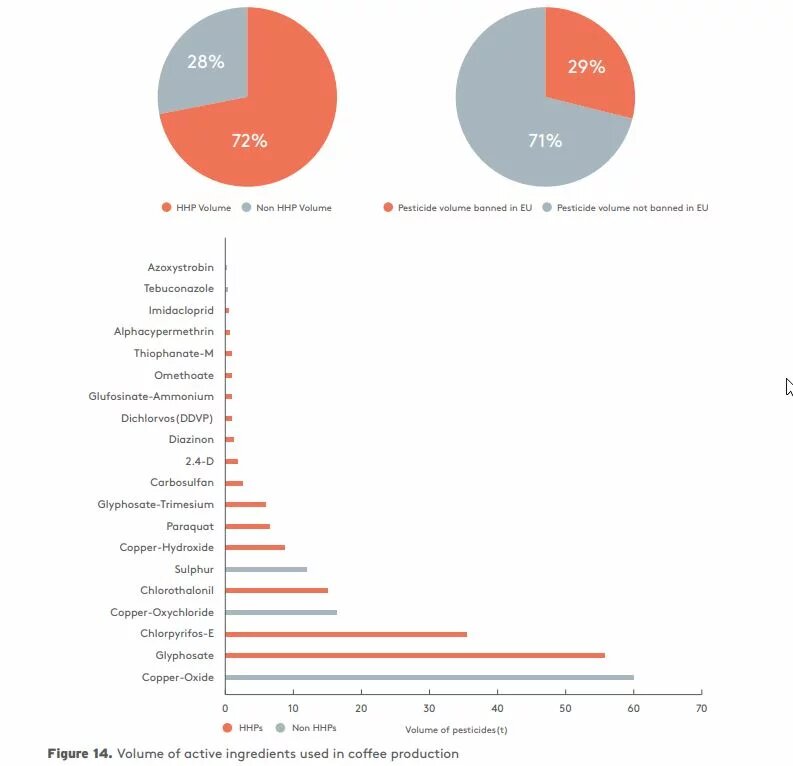

According to the “Highly Hazardous Pesticides in Kenya” report by the Route to Food initiative, a programme of the Heinrich Boell Foundation, both tea and coffee are mentioned as crops that depend on pesticides. Coffee production is mainly reliant on high volumes of highly hazardous pesticides. According to the report, farmers in Kenya use 30 different active ingredients to grow coffee successfully. Seventy-two per cent of the pesticides used in coffee production are harmful hazardous pesticides (HHPs), including glyphosate.

It is time for Kenya to rethink a more sustainable agricultural model centred on benefiting people's livelihoods and well-being and not just the profit of a precious few. It should be a fundamental right for every Kenyan to have healthy food and a thriving environment, and to achieve this, the agricultural and economic policies must be wananchi-centred.

We need to provide enabling conditions for smallholder farmers in Kenya to gradually eliminate products containing harmful ingredients that jeopardise human health and the environment. In the case of coffee production, there is a need to urgently support the farmers, especially women, to access knowledge and resources that help them implement integrated pest management strategies that reduce the reliance on synthetic pesticides. Some of the recommendations emanating from the report are exploring pest control methods like biological controls, crop rotations, and traditional farm practices that prioritise nurturing an agroecological farming approach to build more healthy, diverse ecosystems in their shambas.

Lastly, the government and the private sector must embody and promote more accountability and transparency to ensure that the imperialist and capitalist tendencies are replaced by community-centred values and practices prioritising Kenyans' health, protecting, and safeguarding our environment and more sustainable agriculture. We must move towards transformative change that will improve our lives as a nation. Our lives and the future generation rely on this.

Wanja Muguongo is an organic farmer and eco-feminist