Kenya's diverse soils face interconnected challenges that require tailored solutions for sustainable productivity. Simply increasing the use of synthetic fertilisers is not enough.

Each soil tells a unique story, shaped over thousands—sometimes hundreds of thousands—of years. Most of Kenya’s soils can be classified as tropical due to the country’s warm climate and location near the equator. Tropical soils differ significantly from temperate soils as they are heavily weathered by high temperatures and intense rainfall. These conditions lead to nutrient-leaching, making the soils acidic, with low levels of essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorous, calcium, magnesium, and potassium.

Soils appear red or brown because they are dominated by iron and aluminum oxides. Their low cation exchange capacity limits their ability to retain nutrients. Organic matter in tropical soils breaks down easily, leading to reduced natural fertility and low organic carbon levels. Their texture makes them prone to compaction and erosion if not properly managed. All these challenges require thoughtful interventions for the soils to be productive.

Although 80 percent of Kenya's soils are classified as tropical, they have diverse qualities shaped by factors such as geology, climate, and landscape. These soils range from sandy to clayey, shallow to deep, and vary in fertility. Each type has unique challenges and benefits. For example, sandy soils may drain quickly but struggle to retain nutrients, while clayey soils often hold water and nutrients, but are prone to compaction and poor drainage.

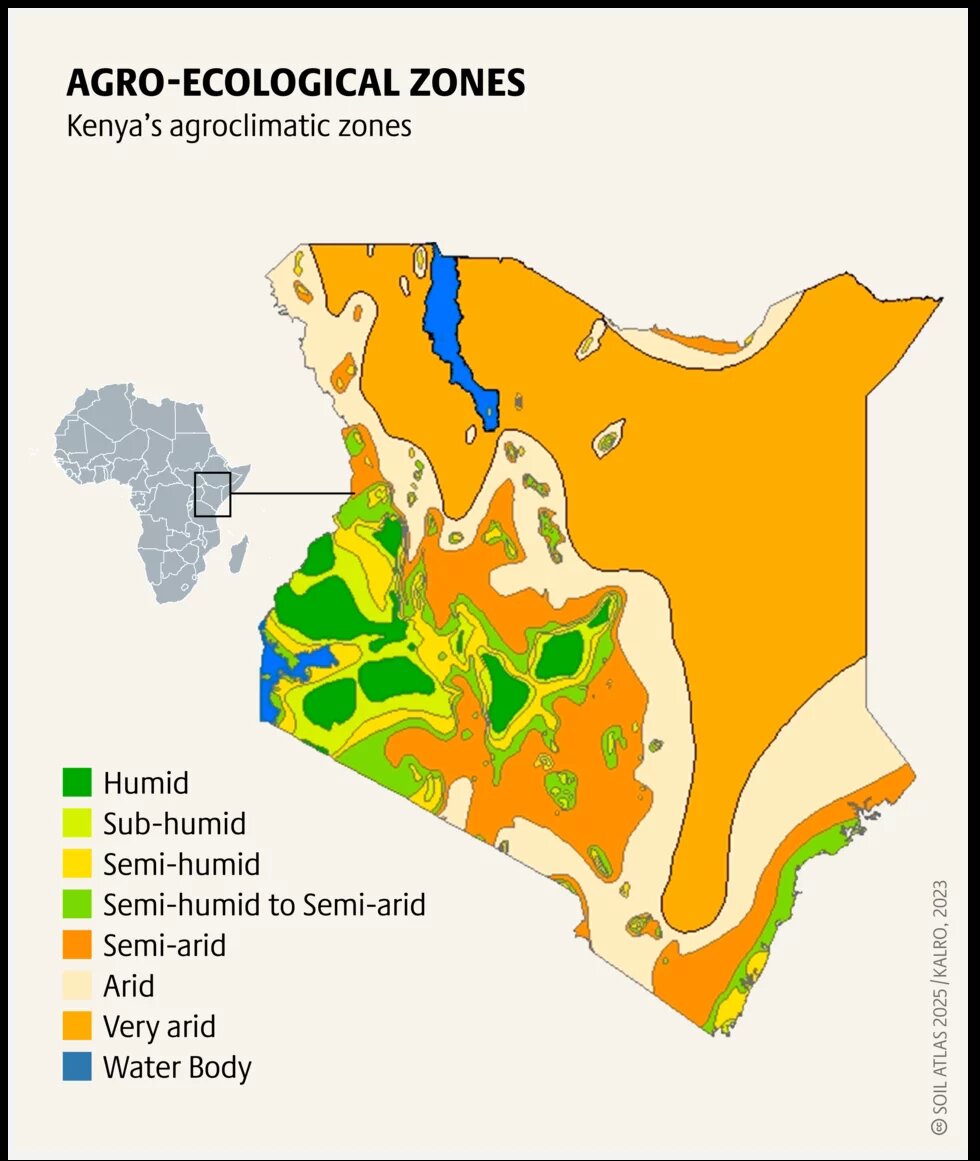

Of the 23 soil types in Kenya’s seven agro-climatic zones, only a few support food production. Zones I-IV, covering 20 percent of the land, receive higher rainfall and have more fertile soils that can support diverse crops. The remaining 80 percent of the land lie in the drier Zones V-VII and can only support drought-tolerant crops. Volcanic soils in high-rainfall areas, fertile highland soils, clay-rich soils in hilly areas, old, weathered soils and heavy clay soils in flat areas are the most farmed among the 23 types.

The volcanic soils are porous and retain water well but are acidic and prone to erosion. They are used for farming tea, vegetables, and pyrethrum. The acidic but fertile highland soils, common in mountainous areas, have good water retention and support crops such as maize, potatoes, bananas and coffee. Sub-humid and hilly zones have clay-rich soils that are compact below the surface. They make farming and root growth harder, but with proper management, can be productive. The old, weathered soils common in parts of western Kenya are nutrient-poor but can yield good crops if nutrients are added and erosion is controlled. Heavy clay soils are found in flood-prone, flat semi-arid regions. They tend to crack when dry and require careful management.

These soil types have diverse shortfalls and addressing them needs site-specific, locally adapted solutions and not a one-size-fits-all approach.

The majority of Kenya's agroecological zones are

characterised as arid or semi-arid. Dryland farming

is a challenge.

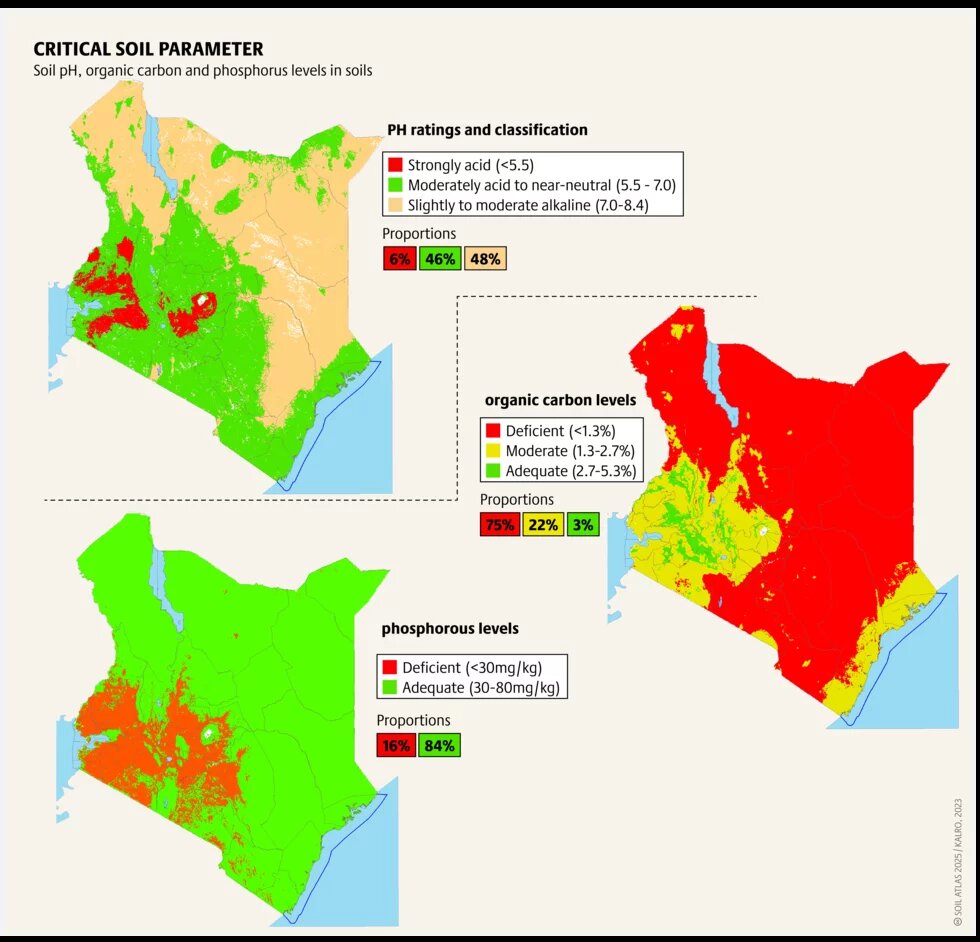

In Kenya, 63 percent of arable land has acidic soils, and 32 percent of that has soils classified as strongly acidic. While some soils are naturally acidic, overuse of synthetic fertilisers has exacerbated the problem. Studies in Kenya’s central highlands and western region show that even high nitrogen fertiliser application in the acidic soils with low organic matter does not boost maize yields above two tons per hectare. However, soils with higher organic carbon and a pH above 6, can produce up to 3.5 tons per hectare, even with lower fertiliser use. Acidic soils fix phosphorus, making it unavailable to plants, and reduce the availability of other key nutrients like potassium. Currently, 80 percent of Kenya’s soils are deficient in phosphorus, and continuous cropping and incorrect application of fertilisers have also depleted nitrogen, potassium, and micronutrients like zinc. To address soil acidity, adding lime or phosphate rock can effectively reduce pH and increase the availability of phosphorus and other nutrients. Balanced fertilisers, combined with organic inputs like compost, can replenish nutrients, improve soil structure and help restore fertility.

Organic carbon deficiency, which affects 75 percent of Kenya’s soils, reduces soil health and productivity. Adding organic matter through compost or biochar is an effective solution.

Salt-affected soils, covering about 40 percent of Kenya’s arid and semi-arid regions. Accumulation of ions such as sodium, calcium, magnesium, and chloride, often caused by poor water management, harden the soil, reduce drainage, and impair crop growth. Addressing these issues involves leaching salts with proper water management, improving drainage, adding gypsum and organic manure, and using deep tillage to enhance soil structure and fertility.

Kenyan soils face various challenges at the same

time-acidic soils often overlap with deficient organic

content and phosphorus levels.

Kenya’s diverse soils face various challenges, but integrated steps such as agroforestry, agroecology, and regenerative agriculture can address these challenges simultaneously. Prioritising them in future soil health policies and management plans can effectively achieve soil health.

This article was published as part of the Soil Atlas Kenya Edition 2025. You can download a copy here