Kenya's worsening soil degradation poses a serious threat to its agricultural future. Redefining soil health through policies that support site-specific solutions is essential for meaningful change in soil management.

In May 2024, the African Soil Health and Fertiliser Summit (ASHF) took place in Nairobi, underscoring the importance of soil health in addressing food security challenges on the continent. For the first time, stakeholders shifted their focus beyond increasing fertiliser use, recognising that tackling hunger and malnutrition requires a deeper and comprehensive approach. Historically, organisations such as the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) and the Gates Foundation have promoted a strategy centered on boosting agricultural inputs to solve these problems. This approach has, however, led to widespread soil degradation, created financial strain on governments through fertiliser subsidies, and plunged many farmers into debt.

One of the resulting guidance documents of the summit, the African Fertiliser and Soil Health Action Plan (2023-2033), aims to increase agricultural production without expanding the area under cultivation, an objective that requires addressing issues like biodiversity loss and environmental degradation. Kenya, which is grappling with unpredictable rainfall, persistent droughts, and degraded soils, is bearing the brunt of these challenges. While the ASHF summit acknowledged the urgency of halting soil degradation, its Soil Health Action Plan offers little concrete guidance for countries to develop long-term sustainable strategies. Instead, the plan seems to favour powerful industrial players like AGRA and the fertiliser giant YARA, sidelining organic solutions that could be more beneficial in the long run.

The ASHF summit’s goal of tripling the production and the use of both synthetic and organic fertilisers by 2034, raises concerns about its true commitment to soil health. Increasing fertiliser use on such a scale seems to contradict the efforts to improve soil health. This raises doubts whether initiatives like the Nairobi Declaration, the 10-Year Action Plan, and the Soil Initiative for Africa can address land degradation and promote sustainable food production.

In 2023, an estimated 298 million Africans experienced undernourishment, a crisis worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic, conflicts, and the ever-growing threat of climate change. Approximately 75 percent of Africa’s land is already degraded, and agricultural GDP is shrinking at a rate of 3 percent annually. The need for sustainable, long-term solutions is urgent.

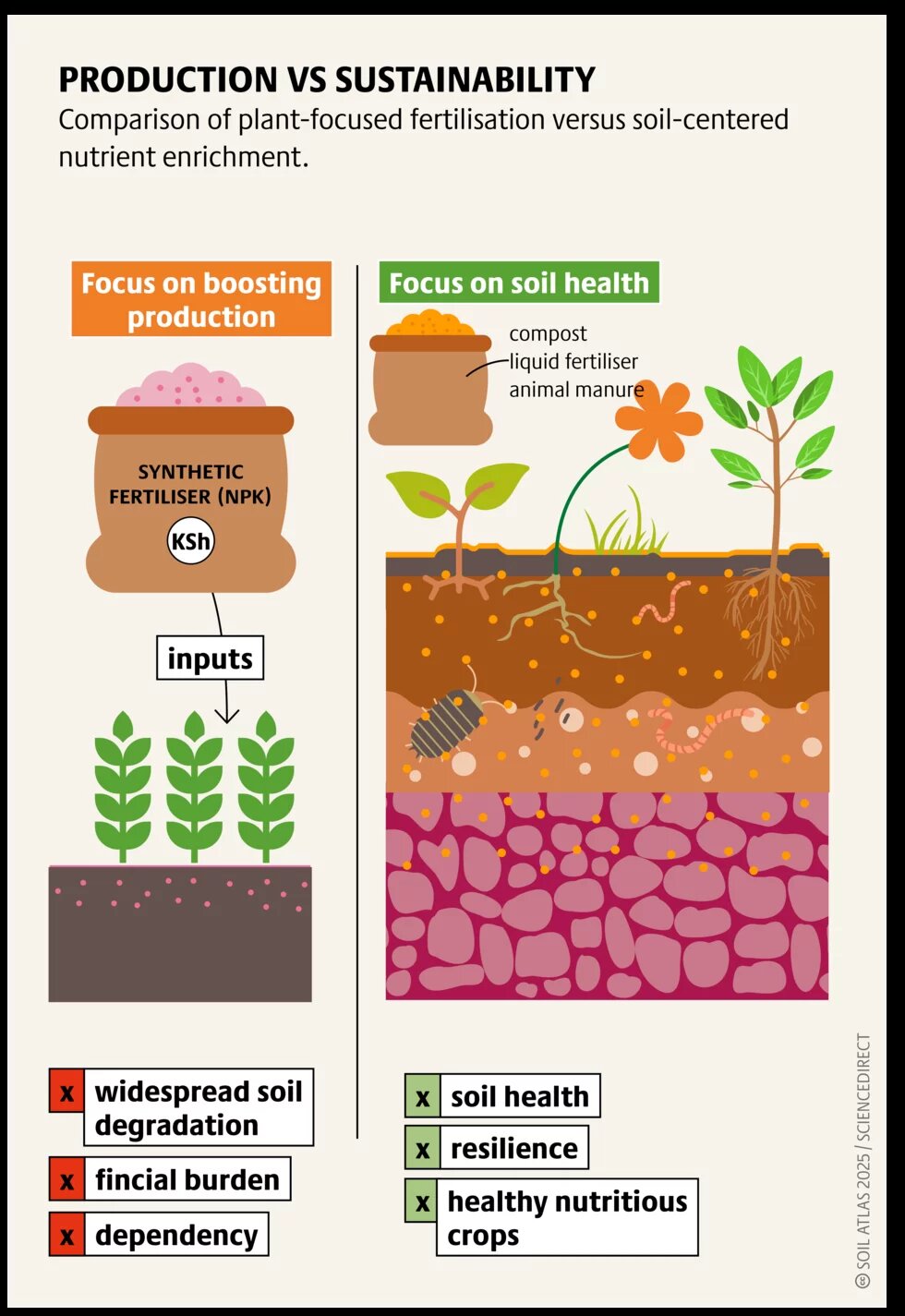

Synthetic fertilisers provide short-term plant nutrition,

while organic fertilisers nourish the soil, enhancing

plant resilience

There is ample evidence suggesting that increasing fertiliser use does not automatically result in better agricultural yields. For instance, despite applying 57 kilogrammes of fertiliser per hectare, Kenya produces less grain than Uganda, which uses only two kilogrammes per hectare. This stark contrast highlights the limitations of relying solely on fertilisers to achieve food security. Furthermore, studies of AGRA projects in Burkina Faso and Ghana reveal that the focus on chemical inputs and high-yield seeds has not significantly improved production or increased farmers’ incomes. Instead, many farmers find themselves trapped in a cycle of debt and poverty due to the rising costs of fertilisers and pesticides. Even Zambia, one of Africa’s highest fertiliser-consuming nations, continues to rank poorly on the Global Hunger Index.

One of Kenya’s priorities has been to reduce reliance on imported fertilisers. The 2023 Kenya Green Hydrogen Strategy and Roadmap aims to replace up to 50 percent of nitrogen fertiliser imports with locally produced green hydrogen-based alternatives by 2032. While this strategy appears to support a cleaner energy transition and reduce import dependency, it raises several red flags. Notably, the plan does not address the role of organic fertilisers, overlooking an essential component of sustainable agriculture. The involvement of international partners, including Germany, introduces additional complexities. Germany’s interest in developing green hydrogen markets as part of its energy transition strategy, partly influenced by geopolitical shifts, raises questions about the long-term viability of green hydrogen-based fertilisers. Will these solutions genuinely contribute to Africa’s food security, or will they simply reinforce harmful agricultural practices under a new label?

Encouragingly, several initiatives in Kenya and East Africa are exploring sustainable pathways to improve soil health. Murang’a County’s Agroecology Policy and Strategy focuses on promoting organic fertilisers, crop diversification, and soil conservation practices. It represents a model for other counties in Kenya to follow. Conversely, Kenya’s National Agroecology for Food System Transformation Strategy (NAS - FST) emphasises the use of organic fertilisers, crop rotation, and integrated pest management to restore soil fertility. Neighbouring Ethiopia has demonstrated the success of community-driven land restoration through its Sustainable Land Management Program (SLMP) which integrates agroforestry and terracing to combat soil erosion and improve fertility. Kenya and other East African countries could adopt similar practices in their degraded regions. Uganda’s vermicomposting projects, which leverage organic waste to produce high-quality fertilisers, provide cost-effective and environmentally friendly solutions. Replicating such efforts in the region could improve soil health and reduce dependency on chemical fertilisers.

Using more fertiliser does not necessarily lead to

higher yields. But it does result in higher costs and

environmental damage

The path forward for Kenya, and indeed for Africa, lies in a genuine commitment to transformative agricultural policies that prioritise soil health. While the ASHF summit may have marked an important step in the right direction, it is crucial to remain vigilant and ensure that the policies discussed translate into tangible actions. Real improvements in soil health, tailored to local conditions and needs, are key to ensuring long-term food security and restoring the dignity and independence of Africa’s farmers.

This article was published as part of the Soil Atlas Kenya Edition 2025. You can download a copy here