The overuse of artificial fertilisers harms soils, nitrogen fertilisers contribute to climate change, and pesticides kill beneficial organisms. Despite this, companies profit from these products and influence governments, blocking essential environmental policies.

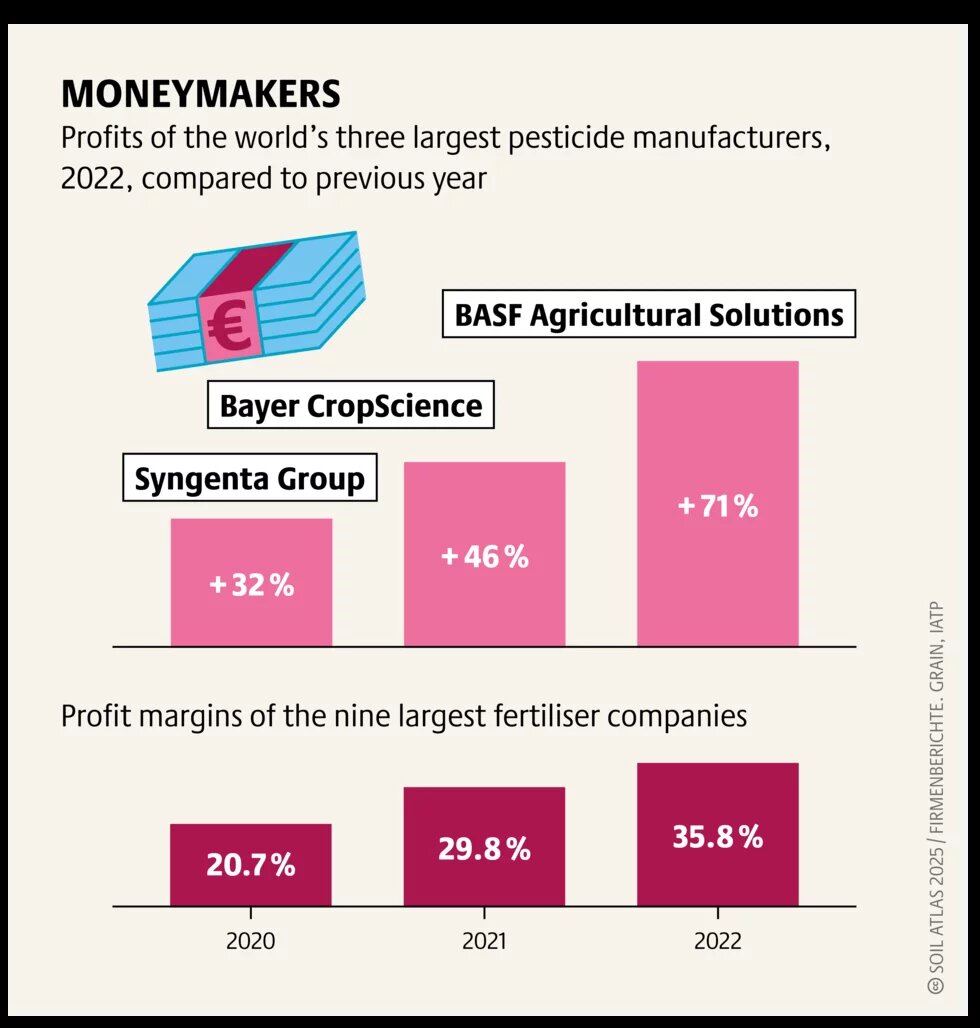

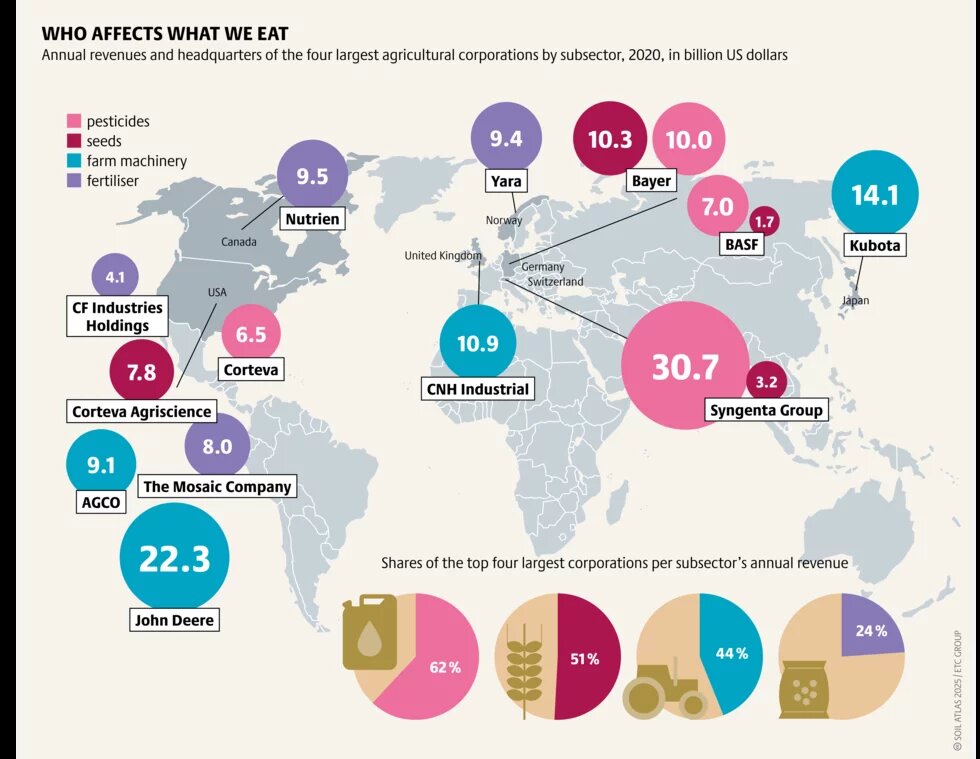

In 2023, almost 73 billion US dollars’ worth of pesticides and more than 200 billion dollars of artificial fertilisers were sold worldwide. High market prices in 2022 meant that the profits of the largest agrochemical manufacturers rose significantly. Since the mid-1990s, the pesticide and fertiliser industries have undergone significant consolidation. Between 1996 and 2009, hundreds of seed and pesticide companies merged into six dominant corporations. By 2020, Syngenta, Bayer, Corteva, and BASF together controlled 62% of the global market. The fertiliser sector has also seen extensive mergers over the past two decades, resulting in major players like Nutrien, CF Industries, Mosaic, and Yara.

While fertiliser and pesticide companies are reaping huge profits, farmers are bearing the brunt of the high cost of production. Between September 2021 and September 2022, the price of nitrogen fertiliser in Kenya increased by 30 percent. To cushion farmers against losses, the government launched an expanded fertiliser subsidy programme with a budget of 23 million US dollars. This significant expenditure limits funds available for other essential public needs.

One reason the trade is so lucrative for the corporations is that their bottomline does not take into account the ecological costs that arise from the use of their products – biodiversity loss, depletion of soil organic matter, and rising soil salinity and acidity.

Many pesticides are banned in the European Union because of their known risks to human health and the environment. But they continue to be sold nonetheless, mainly in the Global South. In 2020, 44 percent of the pesticides used by farmers in Kenya—where Syngenta and Bayer were the main sellers—had been banned in the EU and other countries.

Corporations often use their market power to influence policies. Pesticide and fertiliser companies in the EU have been lobbying against the European Commission’s so-called Farm to Fork Strategy, which is a key plank of the European Green Deal. The agrochemical lobby is influential in Kenya too. It took the country’s regulatory body four years to announce plans to withdraw eight harmful active ingredients after local Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) called for a ban on toxic pesticides that are prohibited in other countries. The industry pushed back, claiming the ban would reduce yields and farmers' incomes, yet it was clear they wanted to protect their profits without considering the harmful effects of their products.

Globally, the pesticide industry gained more political influence through a strategic partnership between the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and CropLife International, an association representing BASF, Bayer, Corteva, FMC, and Syngenta—the top five pesticide companies. The partnership, instituted by a letter of intent signed in 2020, was criticised by numerous civil society organisations that considered it incompatible with FAO’s support for agroecology. In May 2024, the FAO ended its partnership with CropLife.

BASF, Bayer, and Syngenta also generate

income by selling dangerous pesticides banned

in the EU to countries in the Global South

The fertiliser industry is increasingly making its presence felt at international climate policy gatherings. At the 28th UN Climate Change Conference in Dubai, the International Fertiliser Association hosted several events at the Food Systems Pavilion. Fertiliser companies OCI, OCP, Nutrien, and Yara, and pesticide companies BASF, Bayer, and Syngenta, supported a so-called Soil Health Day at the conference, posing as supporters of initiatives aimed at improving soil health. Some of these companies also participated in the 2024 African Fertiliser and Soil Health Summit in Nairobi.

The pesticide and fertiliser industry has responded to growing pressure from civil society and politicians with various strategies while seeking opportunities for profits. Yara, the Norwegian fertiliser company which also operates the world’s largest ammonia trading network, has, for example, announced that it aims to decarbonise its production by reducing carbon dioxide emissions. It plans to use renewable energy to generate green hydrogen, which is used to produce green ammonia. In Kenya, green hydrogen fertiliser production is a central strategy for reducing reliance on synthetic fertiliser imports and lowering agriculture's carbon footprint.

Several large-scale projects are planned, including two major plants near Lake Naivasha, where a green hydrogen fertiliser plant is already operational. Norwegian investment funds and development corporations are also backing green hydrogen projects in Uganda. However, focusing solely on decarbonising production without substantially reducing the use of chemical fertilisers and pesticide risks—or creating the space for more sustainable alternatives—would allow the industry’s core business to continue unhindered.

Digital agriculture, on the other hand, is a completely new business model. Bayer, with its digital platform FieldView, is the current market leader, while Yara intends to build the largest digital agriculture platform in collaboration with IBM. Multinational companies such as Google and Amazon are also pushing into this market.

While precision farming technologies, such as GPS-guided robots, promise to reduce pesticide use, experts warn that control over digital platforms by large pesticide and fertilizer companies may limit farmers' access to affordable solutions and increase their dependence on these corporations.

This article was published as part of the Soil Atlas Kenya Edition 2025. You can download a copy here.