Soil to plate: Kenya's mandatory fortification policy aims to tackle hidden hunger, but true nutritional security lies in restoring soil health and embracing diverse diets for lasting solutions.

When you pick up maize or wheat flour, breakfast cereal, or edible oil, you may notice claims of added vitamins or nutrients. This fortification process has been essential in combating nutrient deficiencies and improving public health. In Kenya, this initiative aligns with the National Food and Nutrition Security Policy (2011), whose aim is to address widespread micronutrient deficiencies stemming from food insecurity, limited diet diversity, and nutrient-scarce soils. However, food nutrient scarcity is directly linked to the state of nutrient deficiency in soils through both mineral uptake and phytochemical production, which in turn influences mineral and vitamin density in food.

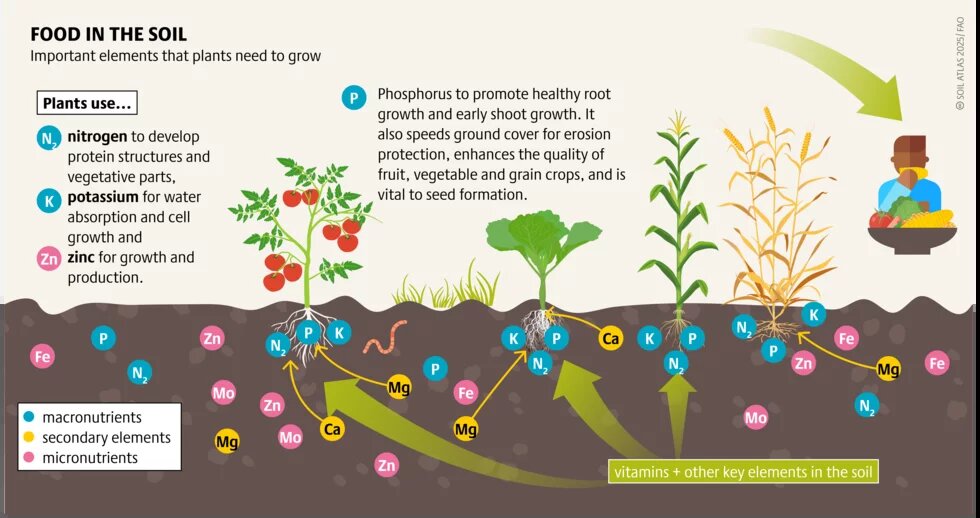

Plants need 18 essential nutrients to grow, 15 of which come from the soil. These nutrients include macronutrients such as potassium, nitrogen, and phosphorus, secondary elements such as calcium and magnesium, and micronutrients such as zinc, iron, and molybdenum. During the growing season, crops strip the soils of these nutrients and soil health directly influences the availability of these nutrients to crops. Inadequate nutrients in the soil directly affect food nutrition content; for example, crops grown in nitrogen-poor soils will have lower protein content. Additionally, studies have also demonstrated a geographical overlap between zinc, selenium, and iodine deficiencies in cultivated soils and the respective deficiencies of the populations in those regions.

Research shows a significant decline in the nutrient levels of crops over the past decades. Studies comparing crops found reductions of between 6 and 38 percent in calcium, phosphorus, iron, riboflavin, and Vitamin C. Protein content in maize dropped by 20 percent between 1921 and 2001 and magnesium levels fell by 25 percent. Declines in zinc, copper, and nickel have been documented in vegetables since the 1970s. These trends highlight the urgent need to address soil health to preserve nutrient density in food.

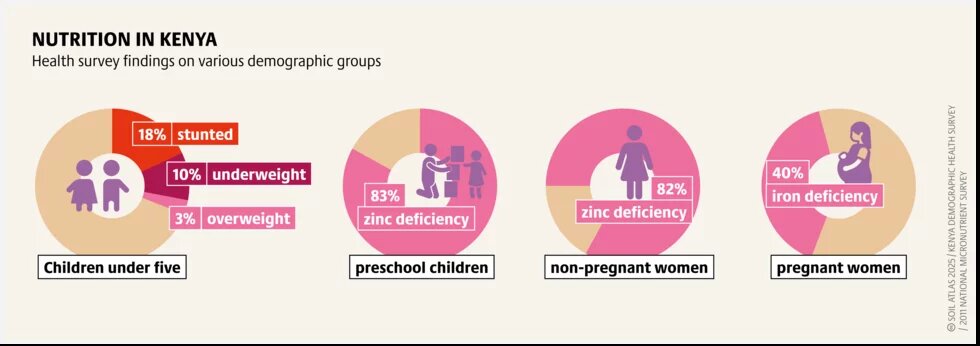

Nutrient deficiencies, or ‘hidden hunger,’ affect billions worldwide, with severe health consequences. Micronutrients are often neglected in this context. Zinc deficiency impairs immune function and growth, Vitamin A deficiency causes preventable childhood blindness and increases infection risks, and iron deficiency leads to anaemia, affecting cognitive function and maternal health. Nutrient demands are high during early development, pregnancy, and lactation, making deficiencies in these periods critical.

Kenya faces a double burden of malnutrition, dispro-portionately affecting vulnerable groups, especially women and children

The immediate stop-gap measures by the Kenyan government’s approach to addressing nutritional security have been four fold: mandatory large-scale food fortification; biofortification of crops at the production level (iron-rich Nyota beans and Vitamin A/beta-carotene-rich orange-fleshed sweet potatoes); supplementation for at-risk groups (iron and folic acid supplements for pregnant women and Vitamin A supplements for infants), and home fortification using nutrient powders or sprinkles for at-risk children. Since 2012, Kenya implemented mandatory large-scale fortification (MLSF), to enrich wheat and maize flours with zinc, iron, and vitamins (A, B1, B2, B3, B6, B12, and folic acid), and edible oils with Vitamin A.

While fortification is a cost-effective way to reach large populations without the need for major dietary changes, it still raises concerns. Over-supplementation risks arise when total nutrient intake from all sources is not monitored because, for most nutrients, fortified food is not the only source of the nutrient. For example, local home fortification methods like mixing grains of maize, groundnuts, sorghum, and millet with legumes in porridge or ugali are popular in many Kenyan households. Moreover, MLSF often fails to reach rural populations reliant on small-scale millers who do not have to comply with fortification regulations.

Lastly, fortification relies on industrial processes, increasing costs and environmental impacts, and fails to address systemic agricultural issues or the root cause of nutrient loss. We risk fortifying food for every nutrient or mineral while missing the point of the food matrix. Food, not nutrients, is the foundation of nutrition.

Sustainable solutions require addressing nutrient deficiencies in the soil, where food production starts. Improving soil health involves sustainable agroecological practices such as companion planting, crop rotation, conservation tillage, and incorporating organic matter. Organic input, including organic matter, not only enriches the soil with nutrients but improves water retention and transmission, improves soil aeration, and fosters microbial diversity, which is critical for nutrient cycling. Healthy soils lead to nutrient-dense crops, which produce equally nutrient-dense food, reducing the need for external fortification.

Agroecological practices also promote crop and livestock diversity on the farm, which ensures a steady supply of different foods and promotes a balanced diet with a wide range of nutrients for communities. A link between crop diversity on the farm and the diet diversity of local communities is well established among subsistence-oriented households and small-scale farmers.

Dietary diversification boosts micronutrient intake by encouraging varied plant- and animal-based foods and should not be neglected. Unlike fortification, it provides a broad spectrum of nutrients and supports human health. Indigenous foods, like African leafy vegetables, are rich in protein, vitamins, and minerals. Farm diversity and agroecological practices support dietary diversity and nutrition sustainably.

Fortification and supplementation do not address the root causes of nutrient deficiencies and hidden hunger. Agricultural policies must consider their impact on nutrition, while health policies must recognise the agrarian origins of many nutrition challenges.

This article was published as part of the Soil Atlas Kenya Edition 2025. You can download a copy here