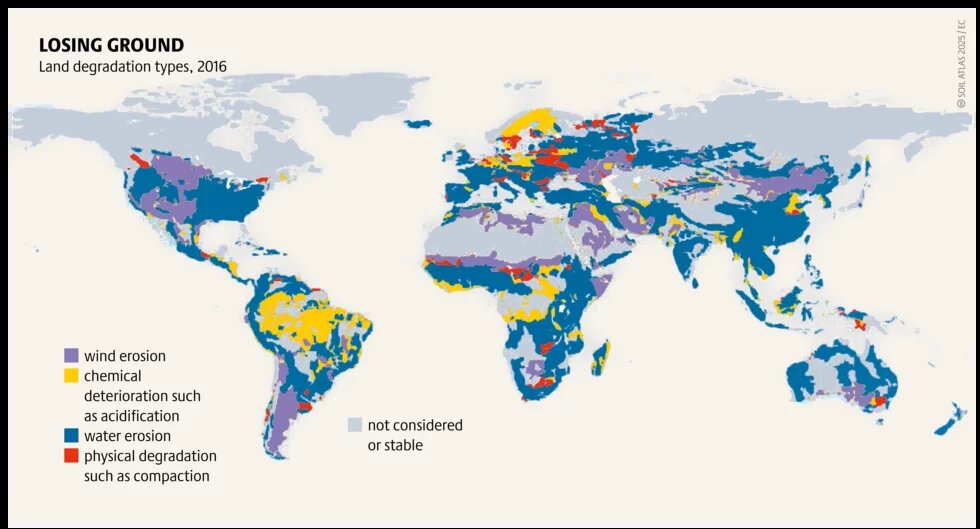

Soil degradation poses a global crisis as it jeopardises food security, livelihoods, and ecosystem health. The situation is worse in East Africa, where over 40 percent of soils are degraded, threatening the region’s agricultural foundation and resilience.

A combination of human activities and natural processes drive this crisis. Overgrazing, unsustainable farming practices, deforestation, and increasingly erratic weather patterns contribute to the depletion of soil quality.

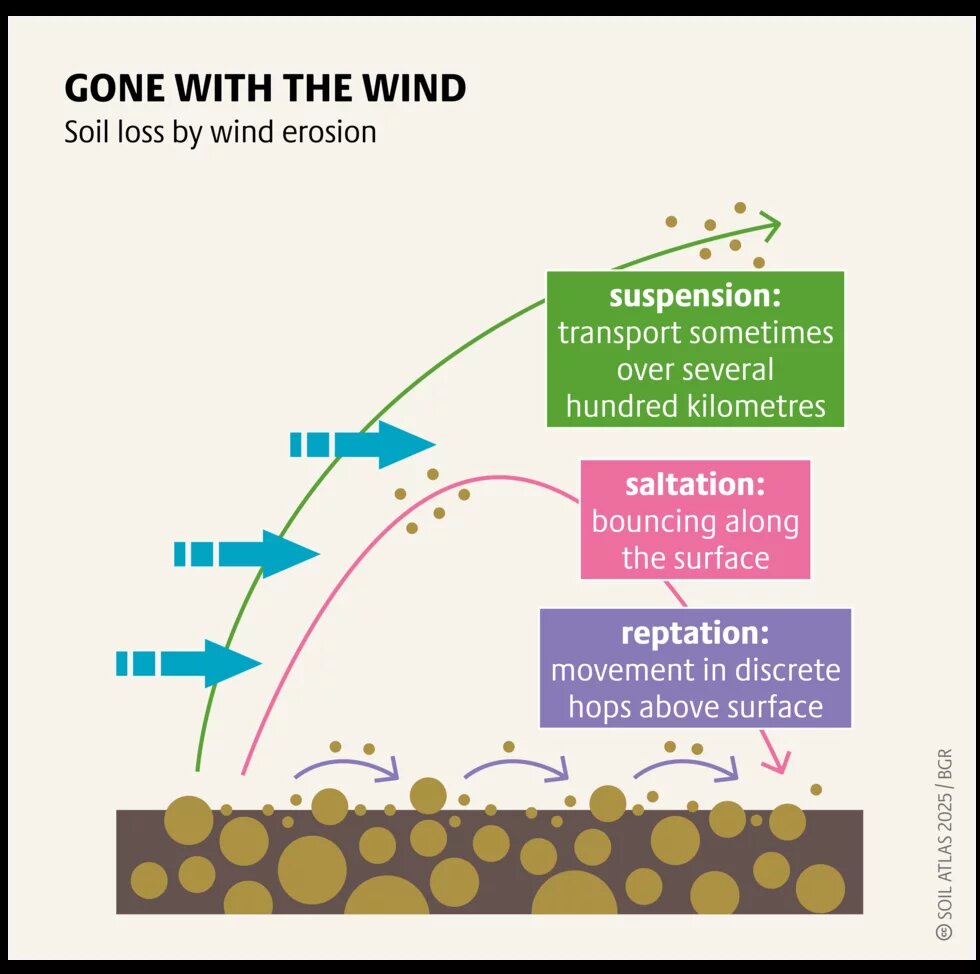

One of the most visible signs of degradation is the erosion of nutrient-rich topsoil, largely caused by water and wind. In Kenya, for example, croplands lose an average of 26 tons of soil per hectare annually to water-induced erosion, with some areas experiencing losses exceeding 90 tons. Overgrazing, especially in dry areas, exacerbates the problem by removing vegetation that protects the soil. Without this cover, the soil becomes vulnerable to erosion and compaction, reducing its ability to absorb water and sustain plant life. Climate change compounds these challenges, as heavy rainfall accelerates soil erosion. Globally, soil erosion costs 400 billion US dollars annually.

In the arid and semi-arid landscapes of northern Kenya and Tanzania, salinisation—the buildup of salts in the soil—is another concern. Poor irrigation practices, such as the use of low-quality water, contribute to this issue. When the water evaporates, it leaves behind salts that gradually accumulate to harmful levels. High evaporation rates and waterlogging also intensify the problem. Approximately 40 percent of irrigated land in Kenya is affected by salinity making it difficult to meet agricultural demands.

Nutrient depletion is another challenge to soil health across East Africa, with over 85 percent of soils being nutrient-deficient. Continuous farming without replenishment, combined with rising soil acidity and poor management practices, has worsened the problem. Organic carbon levels, important for maintaining healthy soil ecosystems, are low. In Kenya, 75 percent of soils fall below sustainable thresholds. This depletion weakens the soil, disrupts microbial communities, and leaves crops vulnerable to disease.

Another issue is soil contamination, hazardous chemicals and heavy metals not only degrade soil health but also pose risks to ecosystems and people. Some of the pesticides used in Kenya are classified as highly hazardous, with long-term consequences to soil productivity and environmental integrity.

Degradation strips people of their

livelihoods, particularly in rural areas

where many rely on agriculture

Soil degradation has a far-reaching impact on communities in East Africa. With over 70 percent of the population relying on agriculture, declining soil fertility threatens food security and livelihoods. In Kenya, degraded soils are estimated to reduce agricultural output by 30 percent, leading to dependency on imports. Land degradation costs the region over 65 billion US dollars annually in lost productivity.

Despite these challenges, there are efforts to counteract soil degradation, with governments, communities, and international organisations working to promote sustainable practices that can help restore degraded landscapes and enhance productivity. Agroecological methods, such as minimising soil disturbance, incorporating organic matter, and diversifying crops, have shown promising results. For instance, agroforestry initiatives taken by the Kenya Agricultural Carbon Project (KACP) in Kenya’s highlands, have reduced soil erosion and improved maize yields, unlike conventional farming methods. Similarly, community-driven conservation efforts like terracing and reforestation, are producing positive results. In northern Tanzania and Kenya’s Rift Valley, such practices have increased crop yields by up to 20 percent, while in Mirema, in Kenya’s Migori County, a Community Forest Association regenerated 50 percent of their denuded forest by planting over 300,000 trees in five years. These examples demonstrate the potential of collaborative approaches to land restoration. However, sustaining these initiatives requires supportive policies and committed investments as well as a strong global partnership.

Innovative technologies are also beginning to play a role as soil mapping and satellite monitoring offer new opportunities for targeted interventions. These technologies can enhance soil restoration efforts despite being in the early stages of development. Programmes such as Kenya’s National Soil Health and Fertility Management Strategy are promising, but achieving meaningful and lasting results will require continued emphasis on restoring soil biodiversity and fertility through sustained policy and financial support. Without this focus, the region risks further degradation which will continue to threaten the resilience of its agricultural systems and the well-being of millions of people.

Open farmland is particularly threatened

by wind erosion, which harms soil quality and

reduces harvest yields in the long term